1 Introduction

We can draw from a rich literature of human-computer interaction (HCI), applied automation in aviation and now emerging human-centered AI (HCAI) to think about medical AI. Many new problems we’re running into now are older problems in disguise. In this article, we’ll draw on premises from the key implementation challenges.

This essay builds on foundational research from Jiang et al and expands their framework with practical medical applications.

2 The Core Challenge

The practical implementation of AI in professional work faces a critical challenge: how to effectively integrate automated systems while preserving human expertise and judgment. While current literature provides theoretical frameworks, we need concrete strategies for real-world application.

Knowledge work automation represents a fundamental shift - AI’s embedded world models make human knowledge scalable beyond the previous limitation of human time.

2.1 The Spectrum of AI Integration

AI tools exist on a spectrum from autonomous to assistive:

- Autonomous systems like Salesforce’s Agentforce can independently handle tasks like prospect outreach

- Copilot systems like GitHub Copilot augment human work by suggesting improvements

- Hybrid approaches combine both, varying by sector and risk profile

Most implementations will likely fall somewhere between fully autonomous and purely assistive, adapting based on the specific context and risk level of the domain.

For example, a medical copilot might autonomously gather drug interaction data while requiring human oversight for final dosing decisions.

For effective integration, well-trained staff is critical. Jeremy Howard’s new law firm, Virgil, aims for bottom-up integration of AI with staff education and AI integration from the get-go.

Similar to law, medicine is a field where risk is crucially minimised. Patient safety must be at the forefront. Jiang et al have identified 3 key tensions we need to solve before we can integrate AI. We’ll largely summarise their fantastic paper while applying it to medicine - please read their full paper and cite them if used.

2.2 A Framework for Integration: Situation Awareness

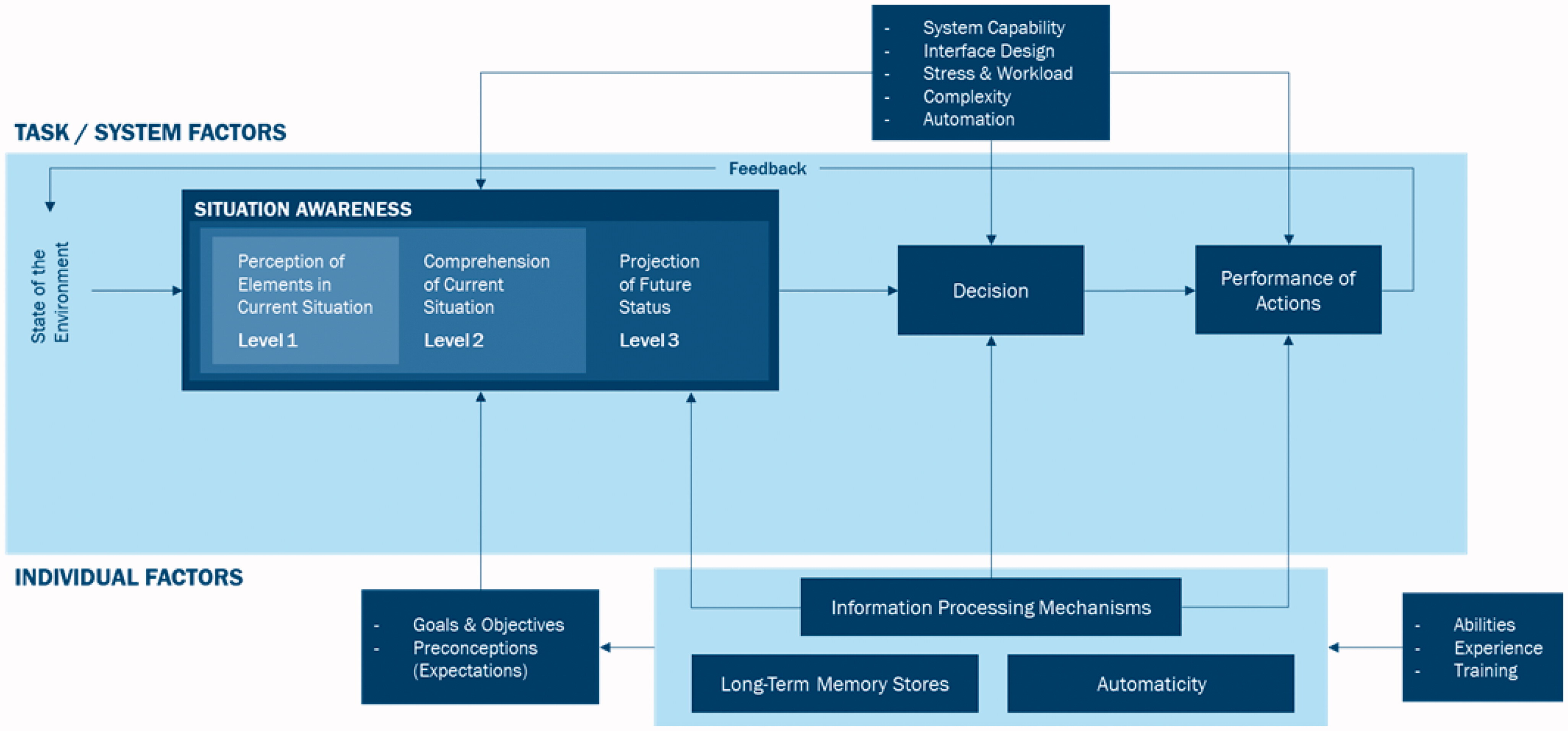

Before examining the tensions in human-AI interaction, we need to understand Situation Awareness (SA). While SA originated in aviation, it offers valuable insights into how humans and AI systems interact.

At its core, SA describes how humans gather and process information to solve problems. Think of it as the foundation that supports decision-making - separate from the decisions themselves.

Even skilled decision-makers can make mistakes if their SA is incomplete or incorrect. Similarly, someone with excellent awareness might still make wrong choices due to gaps in knowledge or training.

SA unfolds in three distinct levels:

- Perception: Noticing key elements in your environment within a specific time and space

- Comprehension: Making sense of what these elements mean

- Projection: Anticipating how the situation might develop

2.2.1 Understanding SA Through a Medical Example

Let’s explore how SA works in a hospital setting:

2.2.1.1 Level 1: Perception

Picture yourself on a ward round. You’re taking in everything around the patient - their appearance, vital signs, recent test results, and examination changes. You notice the electronic medical record (EMR) displaying key data, while also being aware of the broader environment: available nursing staff, family presence, and the treating team. This initial stage builds your mental model of the current situation.

2.2.1.2 Level 2: Comprehension

Now comes synthesis. A doctor combines all these elements into meaningful patterns. For instance, seeing low blood pressure alongside cool extremities and reduced urine output forms a clear picture of poor tissue perfusion - a gestalt that’s more meaningful than any single observation.

2.2.1.3 Level 3: Projection and Planning

This is where experience and implicit learning shine. Based on the patterns recognized, a clinician can anticipate likely developments. They might predict that a patient with worsening respiratory symptoms and dropping oxygen levels will need intensive care soon, allowing them to start preparations early.

2.2.2 Moving Beyond Individual SA: A Complex Systems Perspective

Traditional SA focuses on individual decision-makers, but modern healthcare demands a broader view.

The Distributed Situation Awareness model recognizes that cognition is shared across a network of human agents, technological tools, and now AI systems. This creates a complex environment where the whole system’s capabilities exceed what any individual could achieve alone.

Take a modern aircraft landing. The pilot doesn’t manually calculate wind speeds, drag coefficients, or optimal flap positions. Instead, they interact with a carefully designed system that:

- Processes thousands of data points about weather, aircraft weight, speed, and trajectory

- Automatically adjusts micro-controls like precise flap angles

- Presents only the essential information the pilot needs for decision-making

- Alerts the pilot when specific actions are needed

The pilot achieves “perfect” task awareness not by knowing every calculation, but by understanding the right information at the right time. They trust the system to handle complex calculations while focusing on higher-level decisions about the landing approach.

This is the concept of “transactional memory”. Information is distributed across people and technology. Healthcare has always relied on distributed knowledge:

2.2.2.1 Traditional Distribution

- Clinical guidelines synthesize evidence and expertise across the field

- Subspecialists develop deep knowledge in narrow domains

- Regular updates and revisions reflect new evidence

- Teams combine different expertise for complex cases

2.2.2.2 AI-Enhanced Knowledge Systems

The introduction of AI creates new possibilities for knowledge work:

- Dynamic Knowledge Retrieval

- AI can instantly access and synthesize vast medical literature

- Real-time updates as new evidence emerges

- Contextual retrieval based on specific patient scenarios

- Knowledge Iteration

- AI systems can test hypotheses across large datasets

- Rapid identification of patterns and correlations

- Continuous learning from clinical outcomes

- Knowledge Testing

- Simulation of treatment approaches

- Validation of guidelines across diverse populations

- Early identification of potential risks or limitations

- Knowledge Refinement

- Integration of multiple knowledge sources

- Adaptation to local contexts and populations

- Identification of gaps in current understanding

A completely new balance emerges from AI on distributed situation awareness. AI capabilities can complement human expertise in ways previously impossible.

3 The Medical Context: Three Key Tensions

Medicine provides a crucial case study in AI integration, where patient safety is paramount. Drawing from Jiang et al.’s work, three fundamental tensions emerge:

3.1 Automation vs. Human Agency

You need the right ‘window’ into the assistant AI, with the right information at the right time for a highly trained clinician.

This enables effective human-AI collaboration that doesn’t restrict human agency & correctly uses AI.

3.1.1 The Automation Paradox in Medicine

Consider a future where AI manages:

- Interpreting data-intensive multi-omic analyses

- Pharmacogenomic modeling

- Drug dosing for personalized medicine

Better investigation can help us better characterise disease but this likely requires significant data analysis. This data analysis may mean greater diagnostic accuracy and treatment precision, leading to improved patient outcomes. However, the tension would arise when the intelligent system makes clinical recommendations based upon complex biomarker patterns that are opaque to the human physician and at a level of molecular detail that the human physician cannot fully process, leading to a mismatch in shared understanding between humans and AI. This negates the benefit gained from AI-powered data analysis.

Consider even far sooner future where AI looks through the EMR and flags where treatment deviates from guidelines: The clinician needs to be trained to understand deeply how these AI-driven systems work and also how/when these systems fail. Automation bias refers to the deskilling of staff, shown to disproportionally affect non-specialist doctors in ECG interpretation. This means users need to be substantial domain experts in both medicine & applied AI to safely stay in the loop.

3.1.2 Situation Awareness

To improve human agency, SA is applied as such:

| Current Status (Level 1 SA - Perception) | Reasoning Process (Level 2 SA - Comprehension) | Future Projections (Level 3 SA - Projection) |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

3.1.2.1 Clinical Application: Dermatology AI Assistant

To illustrate these principles, consider an AI system supporting skin cancer screening:

A dermatologist examines a patient with multiple atypical moles. The AI flags one as high-risk melanoma (89% confidence), though it doesn’t match typical patterns. Here are important considerations to retain clinician agency & augment performance.

| Level 1: Perception | Level 2: Comprehension | Level 3: Projection |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

This approach maintains physician control & creates effective AI-physician collaboration by critically:

Making AI decisions transparent in the way the physician thinks (AI SA supports physician SA)

Allowing investigation of AI recommendations because fits into physician SA (AI SA supports physician SA)

3.2 System Uncertainty vs. User Confidence

Consider an AI clinical decision support system. It uses all of the available multimodal data it has (e.g. all EMR data, all imaging, all relevant guidelines) and suggests next actions in a clinical workflow.

Without intelligently handling the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns, the system risks communicating itself with overconfidence, harming physician autonomy and trust.

3.2.1 Clinical Scenario

A 58-year-old patient presents to the Emergency Department with abdominal pain. The hospital’s AI system analyzes available data:

EMR review:

Well-controlled diabetes

Recent normal colonoscopy

Stable vital signs

CT scan suggesting appendicitis

Mildly elevated white blood cell count

Based on these findings and clinical guidelines, the AI system confidently recommends an immediate surgical consultation for an appendicectomy/appendectomy.

However, critical information remains outside the AI’s analysis:

| Known gaps | Potential unknowns |

|---|---|

|

|

The treating physician, drawing on years of clinical experience and subtle patient cues, senses something atypical about the presentation. Rather than proceeding directly to surgery, they pursue additional workup - ultimately discovering a rare parasitic infection contracted during the patient’s recent international travel, which had mimicked appendicitis.

This scenario demonstrates how an AI system that doesn’t explicitly acknowledge uncertainty could prematurely narrow the diagnostic consideration and potentially override valuable physician intuition and clinical judgment. A better system would present its recommendations with appropriate caveats and confidence levels, explicitly noting what information is missing or uncertain, better supporting physician decision-making.

3.2.2 Situation Awareness

Applying SA in this scenario means expressing the uncertainty of the AI system. The extent to which displaying these uncertainty metrics actually improves physician confidence and decision-making remains unclear - would overall outcomes improve if it showed 65% confidence with clear knowledge gaps, versus 85% confidence without acknowledging uncertainties? Does breaking down uncertainty into specific components help or hinder clinical workflow?

An SA-oriented design would structure uncertainty representation across three cognitive levels, helping physicians build a complete mental model of the situation:

| Level 1: Perception | Level 2: Comprehension | Level 3: Projection |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

This approach recognizes that managing clinical uncertainty isn’t passive - physicians need to actively engage with the information, controlling how they view and interpret different uncertainty elements based on their expertise and the specific patient context. By organising uncertainty information around clinical goals and supporting both detailed symptom analysis and broader diagnostic consideration, the system helps physicians develop their own situation assessment while maintaining appropriate confidence in both the AI’s suggestions and their own clinical judgment.

This design philosophy helps harmonize the tension between the AI’s inherent limitations and the physician’s need for confident decision-making, without compromising the crucial role of clinical expertise and intuition.

3.3 System Complexity vs. Perceived Complexity

This final tension underlies the entire human-AI interaction. Modern clinical AI systems are inherently complex, integrating multiple components and data sources. In our ED scenario, the system simultaneously processes:

Structured EMR data (labs, vitals, medications)

Unstructured clinical notes

Imaging data through computer vision algorithms

Clinical guidelines and medical literature

Population-level statistics and outcomes data

As the systems grows in complexity, choosing what to show to clinicians grows in importance.

Like how micro-calculations of flap adjustment doesn’t need to be visible to the pilot, physicians need a balanced view, enough to maintain trust while preventing information overload. The operational complexity can remain manageable with a moderate perceived complexity, despite significant objective complexity.

Objective Complexity: objectively what the system is doing - considering guidelines, statistics, scan results, notes, etc.

Perceived Complexity: the complexity perceived by the clinician:

When we distribute knowledge like trusting the pathologist to accurately read biopsy slides or the MRI machine to function properly, the perceived complexity is reduced to a simple pathology report or conversation with the radiologist.

We aim for reducing the perceived complexity in interdisciplinary conversations to minimise cognitive workload and maximise productivity.

Operational Complexity: refers to the task’s complexity - diagnosing appendicitis may require:

Multiple interdependent decisions (ordering tests, interpreting results, choosing treatments)

Similar presenting symptoms potentially leading to different diagnoses & various decision paths that could lead to the same diagnosis

Need to constantly re-evaluate as new information arrives

This is the hardest balance to strike. Perceived complexity changes vastly based on interface design decisions:

Showing comprehensive evidence supporting the AI’s appendicitis recommendation versus overwhelming the physician with data

Balancing immediate diagnostic suggestions with the need to communicate uncertainty

Determining how much of the AI’s reasoning process to expose

Adapting information density based on case urgency and complexity

3.3.1 Situation Awareness

An SA approach would manage complexity through a layered approach:

| Routine Cases (Low Complexity): | Complex/Atypical Cases (Medium Complexity): | Emergent Situations (High Time Pressure): |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

The system should adapt its complexity presentation based on factors like:

Case urgency

Physician experience level

Time of day (cognitive load may be higher during night shifts)

Case similarity to typical presentations

Level of diagnostic certainty

This framework recognizes that perceived complexity isn’t static - what seems straightforward at the start of a shift might feel overwhelming during a busy night. By structuring information presentation across these varying complexity levels, the system supports physicians’ natural diagnostic reasoning while maintaining their autonomy.

For example, in our appendicitis case:

Initial presentation: Clean interface showing primary findings and straightforward recommendation

As atypical features emerge: System adapts to show more detailed reasoning and uncertainty factors

If emergency intervention needed: Interface shifts to highlight critical decision points and key actions

During detailed review: Allows exploration of full case complexity for learning purposes

This SA-oriented approach helps physicians maintain situational awareness without being overwhelmed by the system’s inherent complexity, ultimately supporting better clinical decision-making while preserving physician autonomy and confidence.

4 Key Takeaways

Medical AI integration requires careful attention to three key tensions:

Automation and Human Agency: For AI to enhance rather than replace medical expertise, clinicians need appropriate visibility into AI systems. This means showing relevant information at the right time while preserving physician autonomy.

System Uncertainty and User Confidence: AI systems must explicitly acknowledge their limitations and gaps in knowledge. Rather than presenting overconfident recommendations, they should support physician decision-making by clearly communicating uncertainties.

System vs. Perceived Complexity: While medical AI systems are inherently complex, their interfaces must balance comprehensive information with usable design. The key is showing enough detail to maintain trust while preventing cognitive overload.

5 Conclusion

The successful integration of AI in medicine depends on understanding how humans and machines can work together effectively. By applying lessons from aviation and human-computer interaction, we can design AI systems that enhance rather than diminish medical expertise.

Situation awareness provides a valuable framework for addressing these challenges. When AI systems are designed to support clinician perception, comprehension, and projection, they can genuinely augment medical decision-making rather than attempting to replace clinical judgment.

The future of medical AI lies not in autonomous systems that work in isolation, but in thoughtfully designed tools that strengthen the doctor-patient relationship and improve clinical outcomes. As we continue developing these systems, maintaining this human-centered perspective will be crucial for realizing the full potential of AI in healthcare.